Keywords

Tuberculosis; Treatment success; Infectious disease

Introduction

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease mainly caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis [1], and it remains a major global health problem [2]. TB represents the second leading cause of death from an infectious disease worldwide after HIV infection [3] and among the top-ten causes of death in children worldwide [4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared TB a global public health emergency in the 1990s, and efforts to improve TB care and control intensified at national and international levels with the development of the directly-observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) strategy [3].

Of the six WHO regions, the highest treatment success rates were reported in the Western Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Mediterranean [5]. The treatment success rate (TSR) was 79% in Africa and 75% in America and Europe [5]. In 2012, Ethiopia reported a total TSR of 91% for all new cases, which was encouraging and above an average TSR of 22 high-burden countries (HBCs) (88%) and worldwide (86%) [6].

The steady spread of multi-drug-resistant (MDR)-TB and extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-TB in many areas indicates that local control measures for TB prevention are unsatisfactory, including the quality DOTS programs [7]. An invasive early detection and standardized management of TB is mandatory to minimize TB burden. The main focus of this study was to determine the level of TSR-associated factors in TB patients.

The WHO has listed 22 HBCs each year since 1997 for TB. According to the 2015 WHO report, 41% of HBCs were African countries, especially sub-Saharan nations including Ethiopia [5]. Worldwide, 3.7% of new and 20% of previously treated TB cases were estimated to be MDR-TB, which is mostly due to poor TB management [3].

Ethiopia is, therefore, highly endemic for TB, where the disease is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity [6]. Ethiopia has applied numerous strategies to prevent and control TB infection, including the expansion of DOTSproviding centers in rural and remote areas and the involvement of private health institutions. TB/HIV collaborative activities were also given due attention to halve morbidity from dual infection. The total time of DOTS shortened from 8 months to 6 months to improve adherence and increase the chance of completing treatment and hence improve TSRs [8].

Methods

Study area

The study was conducted in Wolaita Sodo Town, which is a located 385 km from Addis Ababa and 160 km from the regional capital Hawassa. Wolaita Sodo Town has two hospitals (one public and one private), three health centers, 18 health posts, and 32 private clinics (10 medium and 22 primaries) providing health services. Among these, all health centers, hospitals, and four private medium clinics provide DOTS services [9].

Study design and period

A facility-based retrospective study was conducted from May 1 to 30, 2016. Data on TB patients registered from May 2012 to June 2015 were collected from the unit’s TB registry.

Patients record review

Charts from the public health facilities providing DOTS services in Sodo Town were reviewed for treatment outcome (725 TB patients).

Data collection

Four data collectors with diplomas in nursing and one supervisor with a BSc in public health and with experience in TB studies were recruited.

Data collection procedure

A data collection template was prepared in English by reviewing the TB registry.

Data quality control

Data quality was assured by employing a pre-test for 5% of questionnaires of the calculated sample size in the same facilities and samples were not included in the study. The data collectors and supervisor were trained intensively for two days on data completion using the prepared data collection template. To improve data quality, data collectors were closely supervised, data was checked to ascertain completeness and consistency, and on site corrections were made with close guidance of the principal investigator.

Data processing and analysis

Data were coded and entered into Epi-Info version 3.5.4 to check for inconsistencies before being exported to IBM SPSS version 20 for cleaning and analysis. Logistic regression was employed for data analysis. Bivariate analysis was employed to examine the association between each exposure and outcome variables. To control the effect of confounding factors or to get independently associated variables, each of the variables that was statistically significant at a P-value <0.25 in bivariate analysis was entered into a backward stepwise multiple logistic regression model at 95% CIs as an independent variable and TB treatment success rate. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in both crude and adjusted odds ratio (aOR). Predictor variables of treatment success were reported with aOR and 95% CIs (aOR, 95% CI).

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review committee of the College of Health Science and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

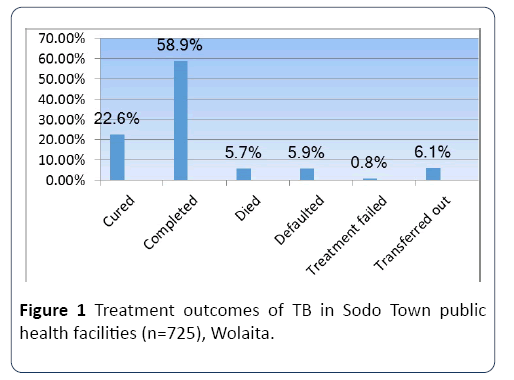

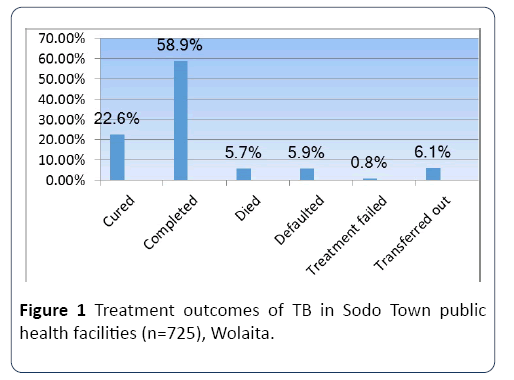

Data were collected from 725 tuberculosis patients attending all public health facilities in Sodo Town. 420 (57.9%) were male, and the mean age of study participants was 28.2 ±13.47 years (range 1-80). Over a third of patients registered 255 (35.2%) were aged 15-24, and the majority (77.1%) were of reproductive age (15-44). Half of TB patients 358 (49.4%) weighed 40-54.9 kg, with a mean weight of 49.42 ±12.96 kg (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Treatment outcomes of TB in Sodo Town public health facilities (n=725), Wolaita.

Overall clinical characteristics

Among registered and analyzed TB patients, a very high proportion (661; 91.2%) were new cases, 41 (5.7%) were transferred in from other facilities and also new for anti-TB treatment, and 18 (2.5%) were relapses. Regarding the form of TB, 292 (40.3%) were sputum smear positive, 230 (31.7%) were sputum smear negative, and 203 (28%) were extrapulmonary TB patients. Sputum smear checkup was positive in 9 (3.1%) patients in month two.

Clinical characteristics of TB/HIV co-infected patients

HIV testing for TB patients preceded the offer of providerinitiated HIV testing and counselling (PITC) and acceptance. Almost all TB patients (717; 98.9%) were tested for HIV and 72 (9.9%) were HIV positive. 51 (70.8%), 55 (76.4%) and 45 (62.5%) HIV-positive TB patients were put on CPT, enrolled to HIV care centers, or started on ART, respectively.

TB treatment outcomes

A successful treatment outcome was achieved in 591 (81.5%) of TB patients, of which 164 (22.6%) were cured and 427 (58.9%) completed treatment. 134 (18.5%) patients were unsuccessfully treated. 43 (5.9%) were treatment defaulters, 41 (5.7%) died, 6 (0.8%) were treatment failures, and 44 (6.1%) transferred to other health facilities.

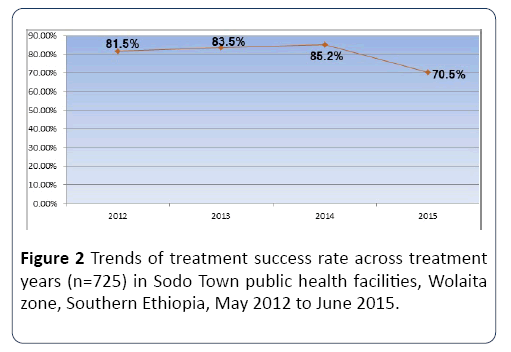

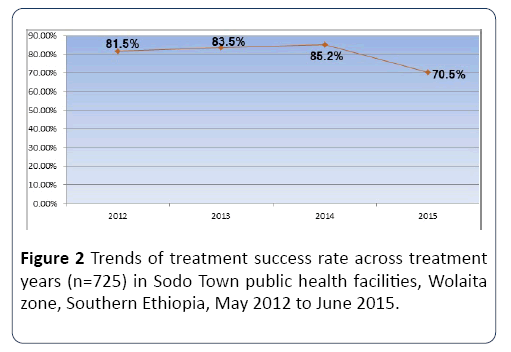

Trends in treatment success rate

TSRs were variable over the study timeframe. Of a total of 160 TB patients enrolled to anti-TB treatment in all four public health facilities in Sodo Town in 2012, 130 (81.2%) were successfully treated and the remaining 30 (18.8%) were poorly treated. TSR slightly increased to 83.5% and 85.2% in 2013 and 2014, respectively, and significantly decreased to 70.5% in 2015. Therefore, the highest TSR was in 2014 and the lowest in 2015 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Trends of treatment success rate across treatment years (n=725) in Sodo Town public health facilities, Wolaita zone, Southern Ethiopia, May 2012 to June 2015.

Factors associated with treatment success rate of TB

Successful treatment was achieved in 343 (47.3%) males and 248 (34.2%) females. Moreover, 367 (50.6%) urban, 224 (30.9%) rural, and 567 (78.2%) TB patients with treatment aids were successfully treated. Regarding to the forms of TB, 250 (34.5%) sputum-positive and 191 (26.3%) sputum-negative patients were treated successfully. 49 (68.1%) of TB/HIV coinfected cases were successfully treated, and the remainder (23; 32%) were poorly treated, with 11 (15.3%) deaths, 6 (8.3%) treatment failures, 1 (1.4%) defaulter and 5 (7%) transfer outs. Likewise, 40 (78.4%) who started CPT, 38 (69%) who had ART, and 34 (75.6%) who started ART were treated successfully (Table 1).

Table 1 Treatment outcomes from TB in Sodo Town public health facilities (May 2012-June 2015).

| Characteristics |

Treatment outcome |

| Successfully Treated |

Not successfully treated |

| Cured N (%) |

Completed N (%) |

Died N (%) |

Defaulted N (%) |

Failure N (%) |

Transferred out N (%) |

Total N (%) |

| Sex |

Male |

100 (13.8) |

243 (33.5) |

22 (3) |

25 (3.4) |

2 (0.3) |

28 (3.9) |

420 (57.9) |

| Female |

64 (8.8) |

184 (25.4) |

19 (2.6) |

18 (2.5) |

4 (0.6) |

16 (2.2) |

305 (42.1) |

| Age category |

0-14 |

5 (0.7) |

56 (7.7) |

1 (0.1) |

3 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.4) |

68 (9.4) |

| 15-24 |

76 (10.5) |

139 (19.2) |

5 (0.7) |

11 (1.5) |

1 (0.1) |

23 (3.2) |

255 (35.2) |

| 25-34 |

49 (6.8) |

115 (15.9) |

11 (1.5) |

15 (2.1) |

4 (0.6) |

7 (1) |

201 (27.7) |

| 35-44 |

22 (3) |

55 (7.6) |

12 (1.7) |

7 (1) |

0 (0) |

7 (1) |

103 (14.2) |

| 45-54 |

9 (1.2) |

40 (5.5) |

4 (0.6) |

2 (0.3) |

1 (0.1) |

2 (0.3) |

58 (8) |

| 55-64 |

2 (0.3) |

14 (1.9) |

4 (0.6) |

4 (0.6) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.1) |

25 (3.4) |

| >=65 |

2 (0.3) |

7 (1) |

4 (0.6) |

1 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.1) |

15 (2.1) |

| Treatment center |

WSTRH |

30 (4.1) |

79 (10.9) |

16 (2.2) |

16 (2.2) |

1 (0.1) |

5 (0.7) |

147 (20.3) |

| SHC |

86 (11.9) |

161 (22.2) |

15 (2.1) |

25 (3.4) |

2 (0.3) |

25 (3.4) |

314 (43.3) |

| GHC |

15 (2.1) |

73 (10.1) |

9 (1.2) |

1 (0.1) |

2 (0.3) |

4 (0.6) |

104 (14.3) |

| WHC |

34 (4.7) |

113 (15.6) |

1 (0.1) |

1 (0.1) |

1 (0.1) |

10 (1.4) |

160 (22.1) |

| Treatment year |

2012 |

29 (4) |

101 (13.9) |

7 (1) |

7 (1) |

1 (0.1) |

15 (2.1) |

160 (22.1) |

| 2013 |

64 (8.8) |

134 (18.5) |

13 (1.8) |

9 (1.2) |

2 (0.3) |

15 (2.1) |

237 (32.7) |

| 2014 |

54 (7.4) |

130 (17.9) |

11 (1.5) |

13 (1.8) |

2 (0.3) |

6 (0.8) |

216 (29.8) |

| 2015 |

18 (2.5) |

61 (8.4) |

10 (1.4) |

14 (1.9) |

1 (0.1) |

8 (1.1) |

112 (15.4) |

| Residence Contact person |

Urban |

108 (14.9) |

259 (35.7) |

27 (3.7) |

35 (4.8) |

2 (0.3) |

22 (3) |

453 (62.5) |

| Rural |

57 (7.9) |

167 (23) |

15 (2.1) |

8 (1.1) |

3 (0.4) |

22 (3) |

272 (37.5) |

| Absent |

11 (1.5) |

13 (1.8) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.4) |

29 (4) |

| Present |

154 (21.2) |

413 (57) |

41 (5.7) |

41 (5.7) |

6 (0.8) |

41 (5.7) |

696 (96) |

| TB category |

New |

145 (20) |

393 (54.2) |

36 (5) |

41 (5.7) |

6 (0.8) |

40 (5.5) |

661 (91.2) |

| Relapse |

4 (0.6) |

10 (1.4) |

1 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.4) |

18 (2.5) |

| Defaulted |

1 (0.1) |

1 (0.1) |

1 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.1) |

4 (0.6) |

| Transfer in |

13 (1.8) |

23 (3.2) |

3 (0.4) |

2 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

41 (5.7) |

| Others |

1 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.1) |

| P/Pos. |

164 (22.6) |

86 (11.9) |

7 (1) |

8 (1.1) |

6 (0.8) |

21 (2.9) |

292 (40.3) |

| Forms of TB |

P/Neg. |

- |

191 (26.3) |

20 (2.8) |

14 (1.9) |

0 (0) |

5 (0.7) |

230 (31.7) |

| EPTB |

- |

150 (20.7) |

14 (1.9) |

21 (2.9) |

0 (0) |

18 (2.5) |

203 (28) |

| Reactive |

8 (11.1) |

41 (56.9) |

11 (15.3) |

6 (8.3) |

1 (1.4) |

5 (6.9) |

72 (100)* |

| HIV status |

Non-reactive |

154 (23.9) |

383 (59.4) |

30 (4.7) |

34 (5.3) |

5 (0.8) |

39 (6) |

645 (100)* |

| Unknown |

2 (25) |

3 (37.5) |

0 (0) |

3 (37.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

8 (100)* |

| TB/HIV Activity |

Started CPT |

| Yes |

8 (15.7) |

32 (62.7) |

6 (11.8) |

3 (5.9) |

1 (2) |

1 (2) |

51 (100)* |

| No |

0 (0) |

9 (42.9) |

5 (23.8) |

3 (14.3) |

0 (0) |

4 (19) |

21 (100)* |

| Linked to ART |

| Yes |

8 (14.5) |

30 (54.5) |

9 (16.4) |

5 (9.1) |

1 (1.8) |

2 (3.6) |

55 (100)* |

| No |

0 (0) |

11 (64.7) |

2 (11.8) |

1 (5.9) |

0 (0) |

3 (17.6) |

17 (100)* |

| Started ART |

| Yes |

7 (15.6) |

27 (60) |

6 (13.3) |

4 (8.9) |

1 (2.2) |

0 (0) |

45 (100)* |

| No |

1 (3.7) |

14 (51.9) |

5 (18.5) |

2 (7.4) |

0 (0) |

5 (18.5) |

27 (100)* |

*Output cross tabbed ‘within’ the variable value.

Age, treatment center, treatment year, forms of TB, CPT initiation for TB/HIV co-infected patients, and sputum smear conversion at the 2nd month were significantly associated with TSR in bivariate analysis (p<0.05). The odds of treatment success was 4.43-times greater for patients treated in 2012 compared to those treated in 2015 (aOR 4.43, 95% CI 1.11-16.33), while TB patients treated in 2014 had a 4.11- times greater chance of succeeding treatment than the reference category (2015; aOR 4.11, 95% CI 1.20-14.12). Pulmonary-negative TB patients had a 4.72-times greater probability of succeeding treatment than extra-pulmonary TB patients (aOR 4.72, 95% CI 1.03-21.67). Likewise, HIV-positive TB patients who started co-trimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT) were 4.8-times more likely to succeed treatment than their untreated counterparts (aOR 4.80, 95% CI 1.01-22.78). Pulmonary-positive TB patients at DOTS initiation with negative sputum smear results at the end of the 2nd month had a 31.73-times greater odds of succeeding treatment than those who were smear positive after completing two months intensive phase therapy (aOR 31.73, 95% CI 5.9-58.63; Table 2).

Table 2 Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with TB TSR in Sodo Town public health facilities, Wolaita zone (May 2012-June 2015).

| Variable |

Category |

Treatment success |

COR (95%CI) |

P- |

AOR (95%CI) |

| Yes |

No |

|

value |

| Sex |

Male |

343 (81.7 ) |

77 (18.3 ) |

1.02 (0.70,1.49) |

0.903 |

|

| Female |

248 (81.3 ) |

57 (18.7) |

1 |

|

|

| Age |

<35 |

440 (84) |

84 (16) |

1.73 (1.17,2.58)** |

0.006 |

1.76 (0.47,6.50) |

| >=35 |

151 (75.1) |

50 (24.9) |

1 |

|

1 |

| Residence |

Urban |

367 (81) |

87 (19) |

1 |

|

|

| Rural |

224 (82.4) |

48 (17.6) |

1.09 (0.74,1.62) |

0.653 |

|

| Contact person |

Present |

567 (81.5) |

129 (18.5) |

1 |

|

|

| Absent |

24 (82.8) |

5 (17.2) |

0.92 (0.34,2.45) |

0.861 |

|

| Treatment center |

WSTRH |

109 (74.1) |

38 (25.9) |

1 |

|

1 |

| SHC |

247 (78.7) |

67 (21.3) |

1.29 (0.81,2.03) |

0.282 |

0.43 (0.08, 2.42) |

| GHC |

88 (84.6) |

16 (15.4) |

1.92 (1.00,3.67)* |

0.049 |

0.30 (0.07,1.29) |

| WHC |

147 (91.9) |

13 (8.1) |

3.94 (2.00,7.76)** |

0 |

0.38 (0.08,1.82) |

| Treatment year |

2012 |

130 (81.2) |

30 (18.8) |

1.81 (1.03,3.19)* |

0.041 |

4.43 (1.11,16.33)* |

| 2013 |

198 (83.5) |

39 (16.5) |

2.12 (1.25,3.61)** |

0.006 |

5.43 (0.74,40.94) |

| 2014 |

184 (85.2) |

32 (14.8) |

2.40 (1.38,4.18)** |

0.002 |

4.11 (1.20,14.12)* |

| 2015 |

79 (70.5) |

33 (29.5) |

1 |

|

1 |

| Weight at initiation |

<20 kg |

28 (87.5) |

4 (12.5) |

1.85 (0.62,5.51) |

0.267 |

1.27 (0.05,32.55) |

| 20-39.9 kg |

62 (80.5) |

15 (19.5) |

1.09 (0.58,2.072) |

0.783 |

1.41 (0.18,11.07) |

| 40-54.9 kg |

297 (83) |

61 (17) |

1.29 (0.86,1.94) |

0.222 |

2.35 (0.57,9.61) |

| 55+ |

204 (79.1) |

54 (20.9) |

1 |

|

1 |

| TB Category |

New |

574 (81.8) |

128 (18.2) |

1.58 (0.61,4.09) |

0.344 |

|

| Retreatment |

17 (73.9) |

6 (26.1) |

1 |

|

|

| Forms of TB |

P/POS |

250 (85.6) |

42 (14.4) |

2.10 (1.34,3.31)** |

0.001 |

1.65 (0.24,11.48) |

| P/NEG |

191 (83) |

39 (17) |

1.73 (1.09,2.76)* |

0.021 |

4.72 (1.03,21.67)* |

| EPTB |

150 (73.9) |

53 (26.1) |

1 |

|

1 |

| HIV Status |

Reactive |

49 (68.1) |

23 (31.9) |

1.28 (0.28,5.81) |

0.751 |

|

| Non-reactive |

537 (83.3) |

108 (16.7) |

2.98 (0.70,12.67) |

0.34 |

|

| Unknown |

5 (62.5) |

3 (37.5) |

1 |

|

|

| CPT initiation |

Yes |

40 (78.4) |

11 (21.6) |

4.85 (1.63,14.45)** |

0.005 |

4.80 (1.01,22.78)* |

| No |

9 (42.9) |

12 (57.1) |

1 |

|

1 |

| Linked to HIV care |

Yes |

38 (69.1) |

17 (30.9) |

1.22 (0.39,3.84) |

0.735 |

|

| No |

11 (64.7) |

6 (35.3) |

1 |

|

|

| Started ART |

Yes |

34 (75.6) |

11 (24.4) |

2.43 (0.89,6.85) |

0.082 |

0.94 (0.22,4.08) |

| No |

15 (55.6) |

12 (44.4) |

1 |

|

1 |

| Smear conversion at 2nd month |

Positive |

3 (33.3) |

6 (66.7) |

1 |

|

1 |

| Negative |

221 (96.5) |

8 (3.5) |

29.28 (11.66,60.16)** |

0 |

31.73 (5.90,58.63)** |

| Not checked |

32 (57.1) |

24 (42.9) |

2.67 (0.60,11.76) |

0.195 |

2.81 (0.59,13.44) |

*P-Value <0.05, **P-Value<0.01

Discussion

Here we reveal an average TSR of 81.5%. Forms of TB, year of treatment, CPT initiation for HIV co-infected TB patients, and sputum smear conversion at the 2nd month were identified as independent predictors of TSR. This study revealed that 40.3% of patients had pulmonary-positive TB, higher than the study finding from Dabat, northwest Ethiopia (29.4%) [10].

TB/HIV co-infection was present in 9.9% of patients, lower than many previous studies [11-16]. This may be due to improvements in community awareness, implementation of multi-sectorial HIV/AIDS prevention activities and geographic, socioeconomic and cultural variability between the study areas. The co-infection rate showed a steady increase throughout three successive years from 2012-2014 (8.8%, 8.9% and 13.4%, respectively) and declined to 7.1% in 2015. It was higher in SSNPT (19.6%) compared to SSPTB (4.5%) and EPTB (6.9%) patients, consistent with a study report from the Gedio zone [15].

The TSR varied across institutions (74.1% to 91.9%), with a total cure and completion rate of 22.6% and 58.9% respectively. The overall TSR reported here was relatively lower than that reported in the Kola Diba Health Center in northwest Ethiopia (85.5%) [17], Woldiya and Dessie Town health institutions (88.1%) [13], and in Dabat (86.7%) [10], which may be due to the geographic variability between the study areas and inclusion of transferred out patients in our study.

The TB success rate was lower than the national average for Ethiopia (89%) [5], an average of 22 HBCs (88%) [5] and also a study from Turkey (91.7%) [18]. However, it was higher than the study conducted in Mizan Aman General Hospital (21.59%) and Gedio Zone (66.44%) of SNNPR, which might be due to transferring a large proportion of TB patients to other treatment centers and not following their respective treatments [15,19]. Transfer out is a known unfavorable (poor) treatment outcome for TB [15,19-21]. 134 (18.5%) of our TB patients were poorly treated and suffered death, default, or transfer out (5.7%, 5.9%, and 6.1%, respectively). The level of unsuccessful treatment outcome was relatively consistent with that reported at the Azezo Health Center, Gondar (19.5%) [16].

An average default rate reported here (5.9%) was higher than a report from Enfraz Health Center in northwest Ethiopia (0.5%) [22] but lower than in Benishangul Gumuz region (8.61%) [23]. This may be due to geographic variability in the study settings, the study period difference, and mechanisms of defaulter tracing. In contrast to the findings of Dessie and Woldia Town health institutions and findings from northwest Ethiopia [13,17], our defaulter rates showed a steady increase across treatment years from 1% in 2012 to 1.9% in 2015.

The treatment failure rate in the current study was 0.8% and steadily increased throughout the study period except for 2013. This was greater than that reported by the Federal Ministry of Health and Debre Markos referral hospital, respectively [24,25].

The overall proportion of deaths (5.7%) was greater than previously reported in different regions of Ethiopia (Addis Ababa (3.7%), Mizan Aman General Hospital (1.22%), Gambela Regional Hospital (3.5%), Gedio Zone (4.33%)) and Brazil (1.7%) [14,15,19,26,27], perhaps due to poorly qualified service provision in the current study setting. However, it was lower than a previous study across Ethiopia (10.1%) [28], Limpopo Province in South Africa (13.6%) and southwestern Nigeria (11.5%) [29,30].

The death rate increased in 2013 (5.5%) compared to 2012 (4.4%) and it decreased in 2014 (5.1%) but showed a significant increase in 2015 (8.9%). The death rate increased from 0.8% in those aged less than 24 years to 1.1% in those aged above 55 years, in line with previous reports indicating that increasing age is a risk factor for death from TB due to increasing co-morbidities and physiological deterioration [31].

Sodo Health Center transferred a relatively high number of TB patients (3.4%) to other DOTS centers, followed by Wadu Health Center (1.4%). In contrast to previous studies [14,19,32], fewer TB patients were transferred out from Wolaita Sodo teaching and referral hospital, probably due to not enrolling TB patients who did not intend to complete treatment in the hospital, even though the hospital is the major diagnostic site of the health facilities in this study. Regarding place of residence, 81% from urban areas and 82.4% from rural areas were successfully treated [33].

This research showed that HIV-infected TB patients were more prone to poor treatment outcomes than non-infected patients, in line with a study in Dessie and Woldia Town [13]. Death, defaulter, treatment failure and transfer out rates of HIV-positive TB patients were 15.3%, 8.3%, 1.4% and 6.9%, with death and defaulter rates higher than previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [34]. This may be due to concomitant administration of anti-tuberculosis and antiretroviral drugs, which can lead to default from pill burden, poor patient compliance, and missing pills due to fear of side-effects. All of these factors can lead to treatment failure, drug interactions, overlapping toxic effects, immune reconstitution syndrome and, ultimately, death.

The TSRs of TB/HIV co-infected patients and HIV noninfected TB patients were 68.1% and 83.3%, which was less than for Gondar University Hospital (50.9% and 45.8%) and lower than for unknown HIV status TB clients in the same research (62.5% vs. 71.2%) [35]. The TSR for TB/HIV coinfected patients was also higher than in Abuja National Hospital, Nigeria (48.8%) [36] but lower than the eastern and southern areas of Tigrai region (71%) [37] and in eight health facilities in Ethiopia (88.2%) [34]. This might be due to low TB/HIV collaborative activities in the current study.

The odds of TSR varied between treatment years in this study. This is in agreement with a report from Addis Ababa, western Ethiopia, Gedio zone of SNNPR, and Metema Hospital of northwest Ethiopia [11,15,26,33]. TB patients treated in 2012 had 4.43-times greater odds of a favorable treatment compared to in 2015, while those treated in 2014 had a 4.11- times greater chance of succeeding treatment than in 2015. This may be due to seasonal attention to TB case management and trained health worker turnover at the facilities.

Pulmonary-negative TB patients had a 4.72-times greater chance of succeeding treatment than extra-pulmonary TB patients, in contrast to previously published finding in the southern region [37], northwest Ethiopia [24] and at Gondar University [28].

HIV-positive TB patients who started CPT were 4.8-times more likely to succeed treatment than their counterparts. Our result supports the hypothesis that CPT initiation prolongs survival by decreasing the incidence of opportunistic infections in all HIV-infected patients [8], hence improving treatment outcomes in TB/HIV co-infected cases [37].

Sputum smear-positive TB patients at DOTS initiation with negative sputum smear results at the end of the second month had a 31.73-times greater chance of succeeding treatment than those who were smear-positive after two months of full intensive phase therapy. This agrees with findings from the southern region of Ethiopia, in which a positive smear at the 2nd month of follow-up was an independent risk factor for poor treatment outcomes. These reports support the notion that any TB patient with a positive smear result at the end of the intensive phase are at risk of poor treatment outcomes and developing MDR-TB, which is a serious public health issue that needs to be addressed [1].

Limitations of the study

The major limitation of this study was that the full range of socio-demographic and clinical variables were not available.

Conclusion

The overall TSR was low, below the WHO TSR target and less than the national TB success rate reported by the WHO in 2015. Health centers exhibited better TSRs than hospitals in the study area. The proportion of deaths was higher in SNPTB than SPPTB and EPTB, while defaulter and treatment failure rates were higher in EPTB and SPPTB than the other forms of TB, respectively. Types of TB, year of treatment, sputum smear conversion by the 2nd month and CPT initiation for HIVpositive TB patients were predictors of TSR.

Recommendations

1. Continuous and close follow-up of TB patients during the course of treatment is recommended.

2. Facilities should follow the overall condition of transferred-out TB patients to other facilities, possibly introducing mechanisms to report their respective treatment outcomes.

3. Treatment of TB-HIV co-infected cases needs attention.

4. We also recommend further studies that include private TB managing institutions, which use a longitudinal design to develop full knowledge and to identify common reasons for unsuccessful treatment outcomes in TB patients.

23556

References

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia ministry of Health (2012) Guideline for clinical and programmatic management of TB, Leprosy and TB/HIV in Ethiopia (5th edn.), Addis Ababa pp: 1-149.

- Tadesse T, Demissie M, Berhane Y, Kebede Y, Abebe M (2011) Two-thirds of smear-positive tuberculosis cases in the community were undiagnosed in Northwest Ethiopia: population based cross-sectional study. PLoS One 6: e28258.

- Biadglegne F, Sack U, Rodloff AC (2014) Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Ethiopia: efforts to expand diagnostic services, treatment and care. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 3: 1-10.

- Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia, m.o.h., Guidelines for clinical and programatic managment of TB,TB/HIV and leprosy in Ethiopia, 2013.

- Tadesse S, Tadesse T (2014) Treatment success rate of tuberculosis patients in Dabat, northwest Ethiopia. Health 6: 306-310.

- Jemal M, Tarekegne D, Atanaw T, Ebabu A, Endris M, et al. (2015) Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients in metema Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A Four Years Retrospective Study. Mycobact Dis 5: 1-7.

- Beza MG, Wubie MT, Teferi MD, Getahun YS, Sisay M, et al. (2013) A five years tuberculosis treatment outcome at kolla diba health center, dembia district, northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective cross_sectional analysis. J Infect Dis Ther 1: 1-6.

- Malede A, Shibabaw A, Hailemeskel E, Belay M, Asrade S (2015) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients and associated risk factors at dessie and woldiya town health institutions, Northeast Ethiopia: A Retrospective Cross Sectional Study. J Bacteriol Parasitol 6: 1-8.

- Asebe G, Dissasa H, Teklu T, Gebreegizeabhe G, Tafese K, et al. (2015) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at Gambella Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: Three-year Retrospective Study. J Infect Dis Ther 3: 1-7.

- Ayele B, Nenko G (2015) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis in selected health facilities of Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A retrospective study. Mycobact Dis 5: 1-9.

- Addis Z, Alemu A, Mulu A, Ayal G, Negash H (2013) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients in Azezo Health Center, North West Ethiopia. Int J Biomed Adv Res 4: 167-173.

- Beza MG, Wubie MT, Teferi MD, Getahun YS, Bogale SM, et al. (2013) A five years tuberculosis treatment outcome at kolla diba health center, Northwest Ethiopia: A retrospective cross-sectional analysis. J Infect Dis Ther 1: 1-6.

- Talay F, Kumbetli S, Altin S (2008) Factors associated with treatment success for Tuberculosis patients: A single center's experiance in Turkey. Jpn J Infect Dis 61: 25-30.

- Sintayehu W, Gebru T, Fiseha T (2014) Trends of tuberculosis treatment outcomes at Mizan-Aman general hospital, southwest Ethiopia: A retrospective study. Int J Immunol 2: 11-15.

- Nemera G (2017) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis and associated factors at Gimbi town health facilities western Oromia, Ethiopia. Nursing Care J 2: 38-42.

- Tefera F, Dejene T, Tewelde T (2016) Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis Patients at Debre Berhan Hospital, Amhara Region, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 26: 65-72.

- Endris M, Belyhun FM, Woldehana E, Esmael A, Unakal C (2014) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at enfraz health center, Northwest Ethiopia: A five-year retrospective study. Tuberc Res Treatment 2014: 1-7.

- Haimanot DTT, Tafess K, Asebe G, Ameni G (2015) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment of short course in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Western Ethiopia: A Ten-Year Retrospective Study. Gen Med (Los Angel) 3: 1-8.

- Esmael A, Moges WGT , Abera H, Endris M (2014) Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients in debre markos referral hospital, North West Ethiopia. Int J Pharmaceut Sci Res

- Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia, M.o.H., Health and health related indicators, 2011.

- Getahun B (2013) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Br J Infect Dis 17: 521-528.

- Belo MTCT, Luiz RR, Teixeira EG, Hanson C, Trajman A (2011) Tuberculosis treatment outcome and socio-economic status; A prospective study Duque de caxias, Brazil. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15: 978-981.

- Tessema B, Muche A, Bekele A, Reissig D, Emmrich F, et al. (2009) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at Gondar University Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. A five-year retrospective study. BMC Public Health 9: 371.

- Gafar MM (2013) Factors affecting treatment outcomes in tuberculosis (TB) patients in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. University of Limpopo.

- Babatunde OA, Elegbede O, Ayodele M, Olusesan JF, Isinjaye AO (2012) Factors affecting treatment outcomes of tuberculosis in a tertiary health center in Southwestern Nigeria. Int Rev Social Sci Humanities 4: 209-218.

- Lawrence M (2009) Tuberculosis treatment outcomes in adult TB patients attending a rural HIV clinic in South Africa (Bushbuckridge). University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, pp: 1-37.

- Moges B, Amare B, Yismaw G, Workineh M, Alemu S, et al. (2015) Prevalence of tuberculosis and treatment outcome among university students in Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective study. BMC Public Health 15: 15.

- Ejeta E, Chala M, Arega G, Ayalsew K, Tesfaye L, et al. (2015) Outcome of Tuberculosis patients under directly observed short course treatment in western Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Ctries 9: 752-759.

- AliEmail SA, Mavundla TR, Fantu R, Awoke T (2016) Outcomes of TB treatment in HIV co-infected TB patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional analytic study. BMC Infect Dis 16: 640

- Cheru F, Girma DMT, Belyhun Y, Unakal C, Endris M, et al. (2013) Comparison of treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients with and without HIV in Gondar University Hospital: a retrospective study. J Pharm Biomed Sci 34: 1606-1612.

- Odume OSOBB (2015) Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at National Hospital Abuja Nigeria: a five year retrospective study. 57: 50-56.

- Belayneh M, Giday K, Lemma H (2015) Treatment outcome of human immunode?ciency virus and tuberculosis co-infected patients in public hospitals of eastern and southern zone of Tigray region, Ethiopia. Braz J Infect Dis 19: 47-51.

- Munoz-Sellart M, Cuevas LE, Tumato M, Merid Y, Yassin MA (2010) Factors associated with poor tuberculosis treatment outcome in the Southern Region of Ethiopia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 14: 973-979.