Awajimijan Nathaniel Mbaba1, Michael Promise Ogolodom2*, Rufus Abam1, Muhammad Akram3, Nengi Alazigha1,Victor Kelechi Nwodo2, Walaa Fikry Mohammed Elbossaty4, Ishmael D Jaja5, Beatrice Ukamaka Maduka6, Robert O Akhigbe7, Ikechi Godspower Achi8, Bolaji Israel Jayeoba9 and Chukwuziem Nnamdi Anene2

1Department of Radiology, Rivers State University Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt Rivers State, Nigeria

2Department of Radiography and Radiological Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nnewi, Nigeria

3Department of Eastern Medicine, Government College University Faisalabad Pakistan

4Department of Chemistry, Damietta University, Egypt

5Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, Rivers State University, Nkpolu-Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

6Department of Medical Radiography and Radiological Sciences, University of Nigeria Enugu Campus, Nigeria

7Department of Radiography and Radiation Sciences, Lead City University, Ibadan Oyo, Nigeria

8Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Rivers State College of Health Science Management and Technology, Rumueme Port Harcourt, Nigeria

9Nigerian Air Force Reference Hospital, Nigerian Air Force Base, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Michael Promise Ogolodom

Department of Radiography and Radiological Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nnewi, Nigeria

Tel: +2348039697393

E-mail: mpos2007@yahoo.com

Received Date: February 08, 2021; Accepted Date: February 22, 2021; Published Date: February 26, 2021

Citation: Mbaba AN, Ogolodom MP, Abam R, Akram M, Alazigha N, et al. (2021) Willingness of Health Care Workers to Respond to Covid-19 Pandemic in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Health Sci J. 15 No. 1: 802.

Keywords

Covid-19 pandemic; Health care workers; Willingness

Introduction

An outbreak of a novel coronavirus disease (abbreviated covid-19) was first reported in December, 2019, in Wuhan City in People’s Republic of China [1,2]. The disease rapidly engulfed the world gripping it with fear and causing unprecedented destruction of lives as well as crippling the global economy. The World Health Organization categorized this novel scourge as a public health emergency on 30January 2020 and a month later it was classified as a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [3]. Nigeria shared the same fate with other nations of the world with loss of many lives and deepening recession. Recovery from the nadir that accompanied this pandemic will take some time especially in low income setting.

The role of the Health Care Workers (HCW) in the struggle against any pandemic cannot be overemphasized. The HCWs are extremely strained during the course of any pandemic [4-6] because of their role as key players in response to a pandemic. Their ability and willingness to report for work despite increased personal risk are essential for pandemic response. By their professional obligation, they must be at their workplaces even if their health is at risk. The delivery of health care services will likely be challenged by the combination of increased patient care demands and staff shortages due to absenteeism induced by perceived threat to lives.Initial estimates in the UK and USA during the covid-19 pandemic suggested that front-line healthcare workers could account for 10–20% of all diagnosed cases of covid-19 [7-9].

The reality of a pandemic response is that health care personnel may be unwilling to work due to perceived inadequate pandemic preparedness of their facility and work place safety. Voluntary absenteeism may stem from fear of infection, duties to one’s family and loved ones [10]. Lack of resources and trust in the management of health care facilities and government may affect HCWs' perceptions and consequently willingness to work.

It cannot be taken for granted that the health care personnel will continue to work despite risk of exposure to emerging infectious diseases. This attitude was observed among health care workers during Ebola epidemic in West Africa [11,12]. Similarly, Stein et al [13], documented the unwillingness of some health workers to place themselves at the risk of exposure to infection during the 2003 SARS epidemic and the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In a survey of hospital employees in Germany during influenza pandemic, Ehrensteinetal [14] found 28% of professionals (clinical and non-clinical) may abandon work in favour of protecting themselves and their family. Furthermore, unwillingness to respond to a pandemic has also been demonstrated among health care workers in Nigerian and Ethiopian studies during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic [2,15].

Perception of risk may greatly predict human attitude. During a pandemic a health personnel may be unwilling to work due to a number of perceived risks. There is need to know the barriers that may result in absenteeism and to establish interventions to mitigate them. To ensure effective running of health care services despite the challenges posed by the pandemic, it is essential that health care workers are willing to work.There is dearth of data on factors that may influence willingness of HCWs to work during a pandemic, especially in resource poor setting like ours. The aim of this study was to identify the various factors that can influence the health workers willingness to discharge their duties during a pandemic and to suggest options for changing the attitude of those who might be unwilling to work to facilitate evidence-based disaster planning.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey targeting healthcare workers in Port Harcourt, Nigeria was conducted. The data collection instrument was a 17 items structured and self-completion questionnaire designed by the authors according to the aim of the study. Twenty copies of the printed version of the questionnaire were pre-tested among selected healthcare workers before the commencement of data collation. A Cronbach alpha reliability value of 0.86 for internal consistency was obtained. The validity of the questionnaire was calculated using the index of item objective congruence (IOC) method used by previous authors [2,16]. The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by calculating the IOC. Based on the index parameters, an IOC score >0.6 was assumed to show excellent content validity. All the scores obtained in this study for all the items of the questionnaire after IOC interpretation were >0.6.

The questionnaire consisted of six parts

Part 1: It includes the set of elements describing the Sociodemographic variables of the respondents that include age, gender, years of experience, practice location, health sector, and profession.

Part 2: It includes a set of elements that measure the knowledge of healthcare workers of their responsibilities and jobs.

Part 3: It consists of a set of elements that measure Respondent's risk perception towards the Covid-19 pandemic.

Part 4: Includes a set of elements that measure Respondents work pattern and workplace safety during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Part 5: Includes knowledge of Respondents means of transportation to work and place of residence during this pandemic.

Part 6: Includes identifying Ways to increase the respondents willingness to work and mitigate absenteeism from work during this pandemic.

Both the printed and an electronic version of the questionnaire were administered to the respondents. The electronic version designed using the Enketo Express for Kobo Toolbox was used to obtain information from the participants who were not proximity with the researchers. The link of the electronic version of the questionnaire was sent to the respondents through their email addresses and WhatsApp platforms where they had access to fill the questionnaire. The printed version was administered to the respondents by direct issuance. The completed copy of the questionnaire was retrieved immediately after being filled out by the respondent while the responses from the electronic version were collated in an electronic spreadsheet.

The purpose of the study was explained in the questionnaire and the respondent’s consent to participate in the study was sought before his participation. The respondent’s private information was treated with confidentiality. The respondents were instructed to fill the questionnaire just once to avoid duplication of data and their participation in this study was entirely on voluntary bases.

Statistical analysis

The data generated in this study was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 (SPSS Inc, ILL, USA, 2003). The data were analyzed using descriptive statistical tools such as frequencies and percentages and presented in tables and charts. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the relationship between the respondents’ years of experience and their willingness to go to work during pandemic. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic variables of the respondents

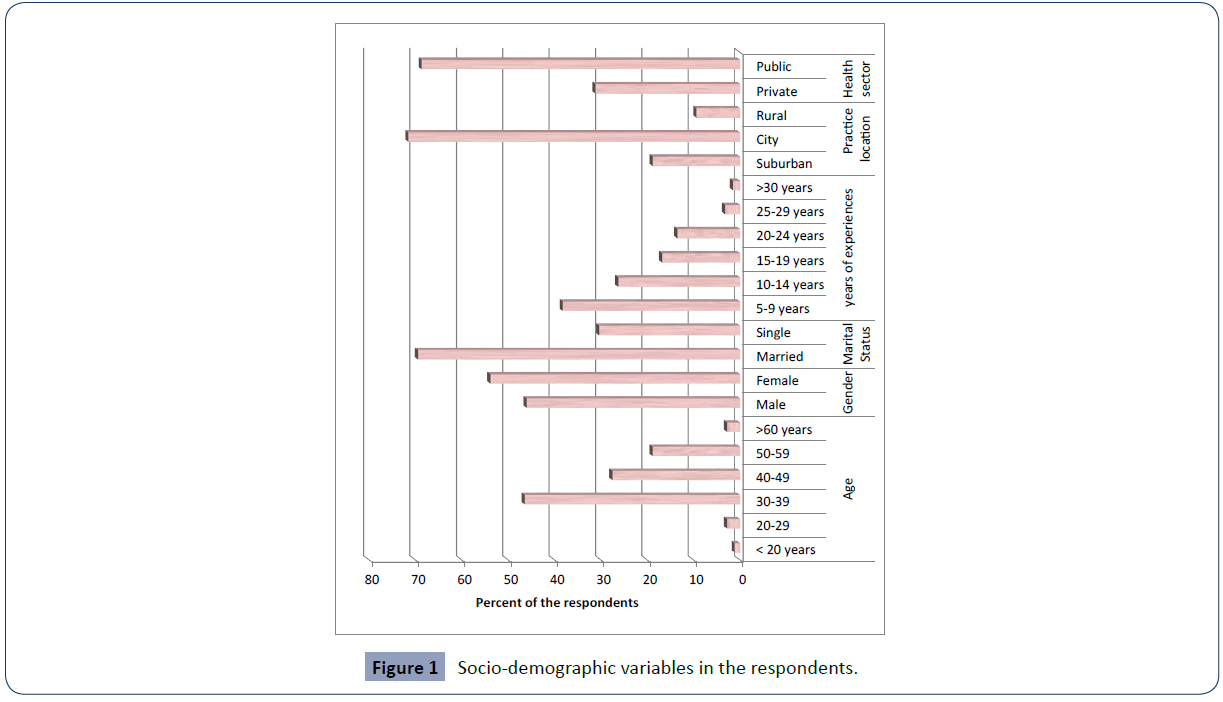

Out of 243 respondents, majority 46.5%, (n=113) were within the age group of 30-39 years. The respondents were made up of 46.1% (n=112) males and 53.9 % (n=131) females. A greater proportion of the respondents 69.55% (n=169) were married while 30.45% (n=74) were single. A majority of 38.27% (n=93) of the respondents had 5-9 years working experience. The respondents predominantly (71.6%), n=174) practiced in cities. The respondents were largely public sector employees (68.72%, n=167) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Socio-demographic variables in the respondents.

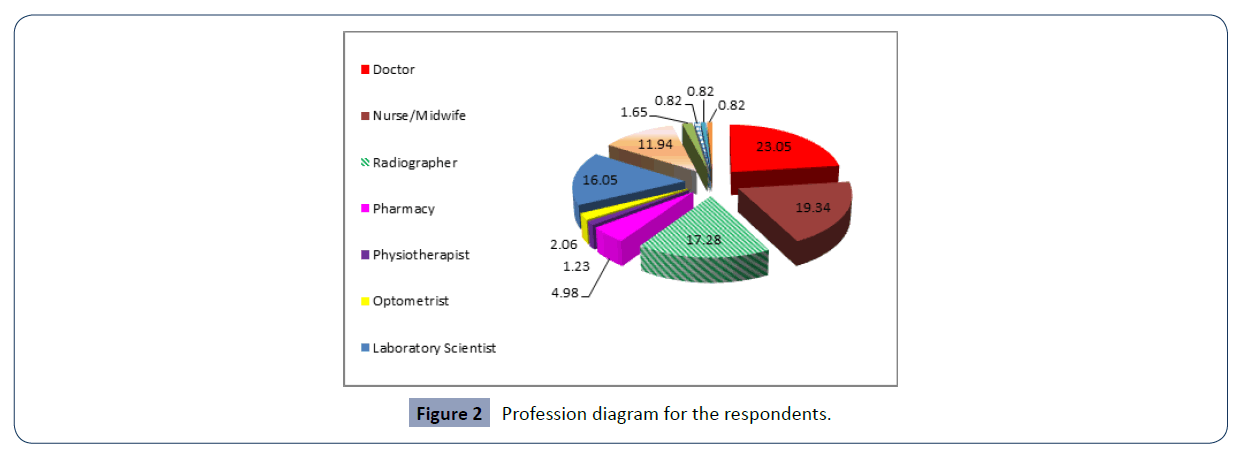

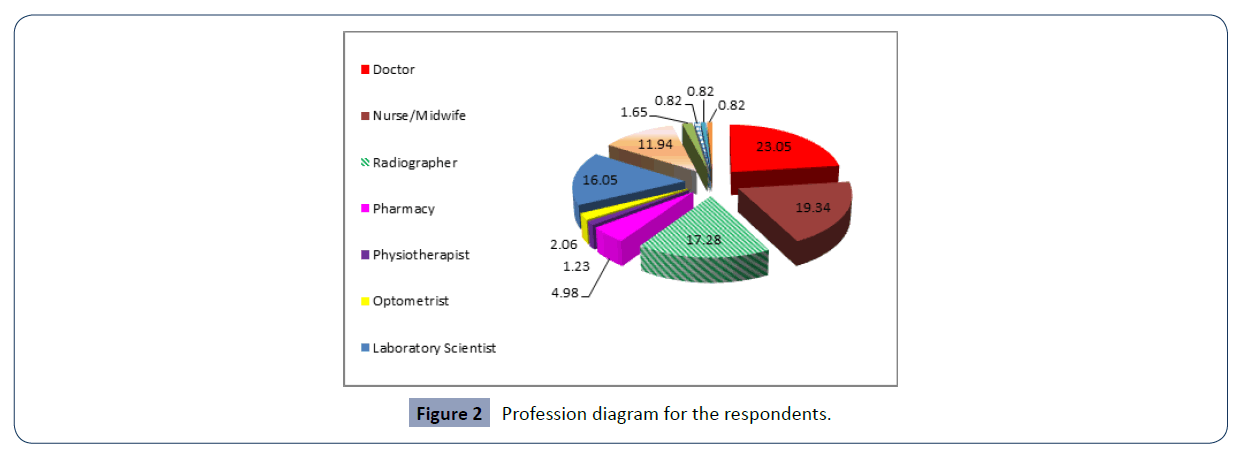

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the respondents according to their professions. A majority of the respondents 23.05% (n=56) were medical doctors, followed by nurse/midwives 19.34% (n=47) and the least were cleaners, admin and clerical staff and drivers, which was 0.82% (n=2) each respectively (Table 1).

Figure 2 Profession diagram for the respondents.

| Risk Perception |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| a. Do you see yourself at risk of infection by going to work these days? |

|

|

| Strongly Agree |

131 |

53.91 |

| Agree |

79 |

32.51 |

| Not sure |

31 |

12.76 |

| Disagree |

2 |

0.82 |

| Strongly disagree |

- |

- |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| b) Health workers are prone to having the infection? |

|

|

| Strongly Agree |

196 |

80.66 |

| Agree |

46 |

18.93 |

| Not sure |

1 |

0.41 |

| Disagree |

- |

- |

| Strongly disagree |

- |

- |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| c) There is no known risk in coming in contact with a Covid-19 patient? |

|

|

| Strongly Agree |

10 |

4.15 |

| Agree |

6 |

2.47 |

| Not sure |

12 |

4.94 |

| Disagree |

34 |

13.99 |

| Strongly disagree |

181 |

74.49 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| d) Is your willingness to go to work these days affected by Covid-19 pandemic? |

|

|

| Strongly Agree |

50 |

20.58 |

| Agree |

138 |

56.79 |

| Not sure |

42 |

17.28 |

| Disagree |

4 |

1.65 |

| Strongly disagree |

9 |

3.7 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| e) Is your willingness to go to work these days affected by Covid-19 pandemic? |

|

|

| Strongly Agree |

153 |

62.96 |

| Agree |

62 |

25.51 |

| Not sure |

15 |

6.17 |

| Disagree |

9 |

3.7 |

| Strongly disagree |

4 |

1.66 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| f) Do you think having a number of dependents can affects ones willingness to work during a pandemic like covid-19? |

|

|

| Strongly Agree |

13 |

5.35 |

| Agree |

12 |

4.93 |

| Not sure |

10 |

4.12 |

| Disagree |

69 |

28.4 |

| Strongly disagree |

139 |

57.2 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| g)Do you think your family is prepared to function without you? |

|

|

| Strongly Agree |

13 |

5.3 |

| Agree |

12 |

4.9 |

| Not sure |

10 |

4.2 |

| Disagree |

69 |

28.4 |

| Strongly disagree |

139 |

57.2 |

| Total |

243 |

4.2 |

Table 1 Respondent’s risk perception.

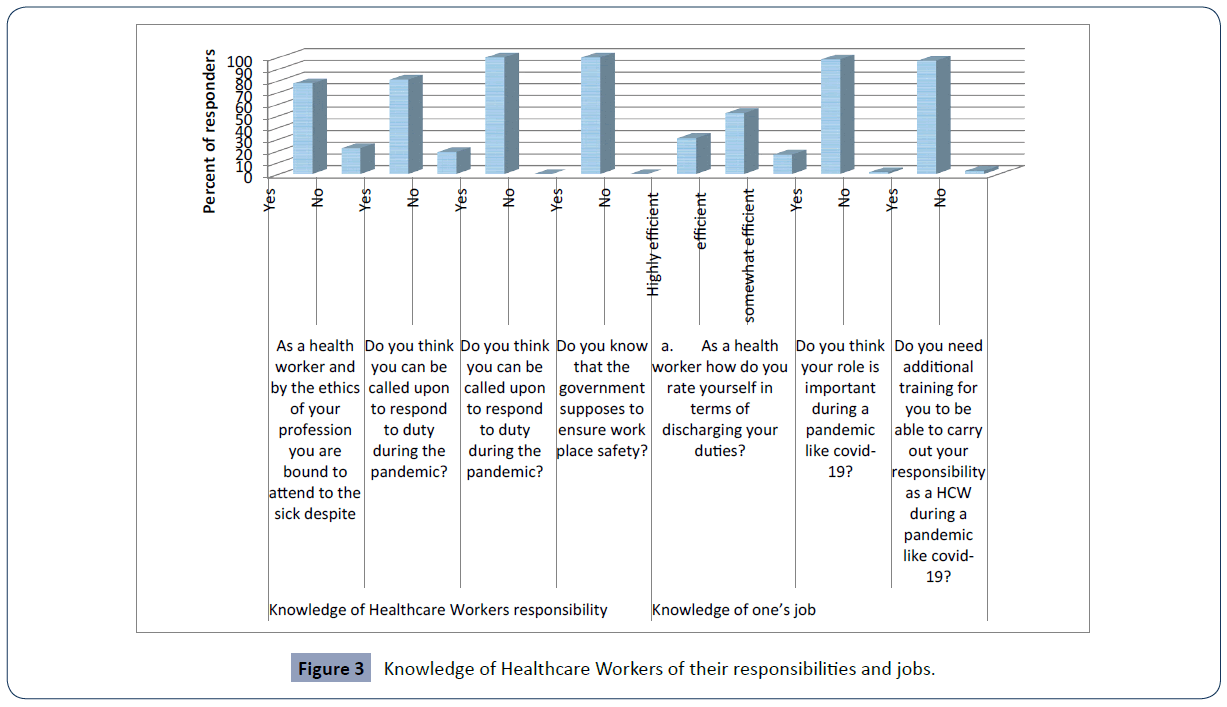

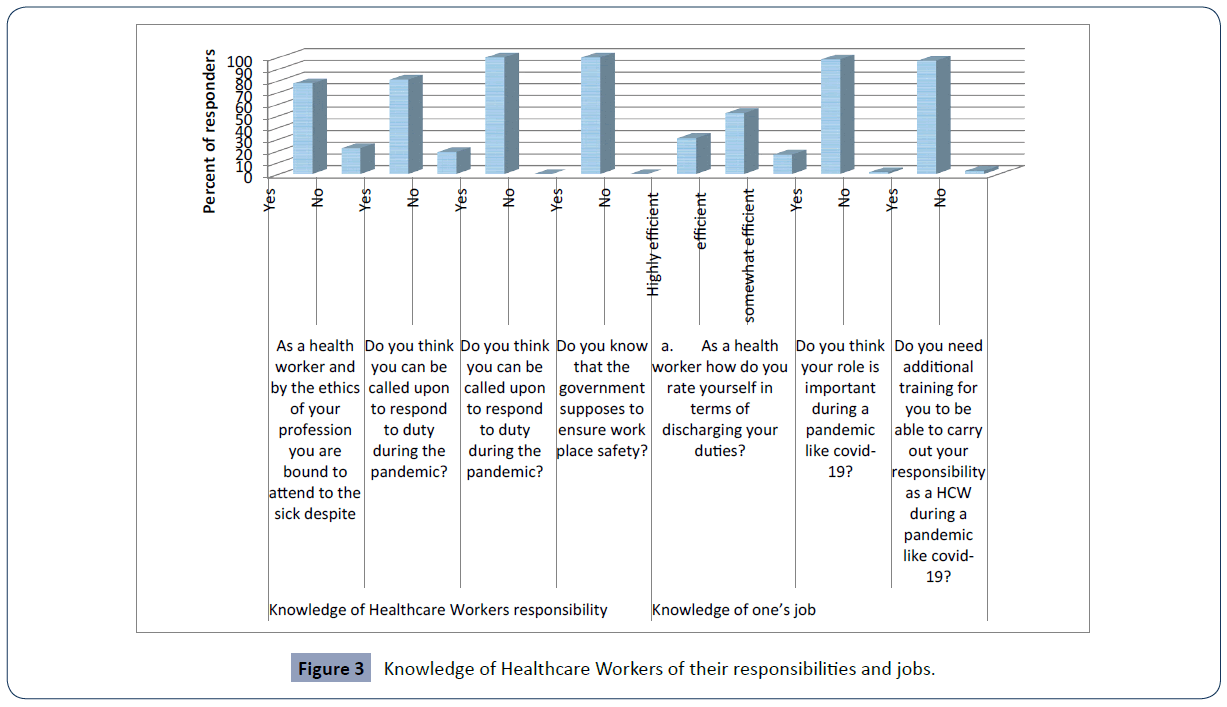

Knowledge of healthcare workers of their responsibilities and jobs

Table 2 shows the respondent’s knowledge of their responsibility and job. A majority of the respondents 77.78% (n=189) agreed that they are bound by the ethics of their profession to attend to the sick despite risk. A majority of the respondents 81.07% (n=197) agreed that they could be called upon to respond to duty during the pandemic. Greater proportion of the respondents 52.26% (n=127) rated themselves to be efficient in terms of discharging their duties. A majority 98.35% (n=239) of the respondents agreed that their roles are important during a pandemic like covid-19 (Figure 3).

| Pattern and work place safety |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| a.Working pattern |

|

|

| How many days in a week do you go to work since the beginning of thepandemic- |

|

|

| one |

2 |

0.82 |

| two |

16 |

6.58 |

| three |

106 |

43.62 |

| four |

96 |

39.51 |

| five |

23 |

9.47 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| How many days in a week do you normally go to work before this pandemic – |

|

|

| one |

1 |

0.41 |

| two |

6 |

2.48 |

| three |

18 |

7.41 |

| four |

97 |

39.9 |

| five |

121 |

49.79 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Do you have to change your working pattern for fear of contacting the infection? |

|

|

| Yes |

227 |

93.42 |

| No |

16 |

6.58 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| b. Work place safety |

|

|

| Do you think your health care facility is prepared to handle and manage covid-19 outbreak? |

|

|

| Strongly disagree |

179 |

73.66 |

| Disagree |

39 |

16.05 |

| Somewhat agree |

8 |

3.29 |

| Agree |

9 |

3.7 |

| Strongly agree |

11 |

3.3 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Do you think your work place Safety is adequate? |

|

|

| Strongly disagree |

106 |

43.62 |

| Disagree |

89 |

36.63 |

| Somewhat agree |

30 |

12.35 |

| Agree |

16 |

6.58 |

| Strongly agree |

2 |

0.82 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Hospital infection control policy is adequate? |

|

|

| Strongly disagree |

77 |

31.69 |

| Disagree |

56 |

23.05 |

| Somewhat agree |

103 |

42.32 |

| Agree |

7 |

2.94 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| There is the possibility of getting the infection in the hospital: |

|

|

| Strongly disagree |

10 |

4.12 |

| Disagree |

6 |

2.47 |

| Somewhat agree |

8 |

3.29 |

| Agree |

92 |

37.86 |

| Strongly agree |

137 |

52.26 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Do you use PPE at work? |

|

|

| Yes |

112 |

46.09 |

| No |

131 |

53.91 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Do you wear your face mask while at work? |

|

|

| Yes |

198 |

81.48 |

| No |

45 |

18.52 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| How do you relate with your colleagues at work these days of the pandemic? |

|

|

| Freely (No restriction) |

39 |

16.05 |

| Restricted |

189 |

77.78 |

| No relation at all |

15 |

6.17 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Has any of your colleague been infected by the covid-19? |

|

|

| Yes |

45 |

18.52 |

| No |

198 |

81.48 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| What is the role of the admin to cater for the infected colleague- |

|

|

| major role |

56 |

23.6 |

| some role |

107 |

44.03 |

| none |

80 |

32.91 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| In case of death who takes care of the colleagues dependents. |

|

|

| You are on your own |

197 |

81.07 |

| government assist |

16 |

6.58 |

| no government assistance |

30 |

12.35 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

Table 2 Respondents work pattern and workplace safety.

Figure 3 Knowledge of Healthcare Workers of their responsibilities and jobs.

Risk perception for respondents

From Table 1, the respondents’ perception of risk was evaluated in table 1 and the majority 53.91% (n=131) strongly agreed that they were at risk of infection by going to work during the pandemic. Also, 56.79% (n=138) of the respondents agreed that covid-19 pandemic have greatly affect their willingness to go to work. Chi-square test was done to evaluate the relationship between the years of experience and the respondent’s willingness to work during the pandemic and the result revealed that there was statistically significant relationship between years of experience and respondent’s willingness to work (X2=234.34, p=0.023).

Respondents work pattern and workplace safety

With respect to the respondents’ working pattern and work place safety assessed in table 2, greater proportion of the respondents 43.62% (n=106) said they went to work three days per week during the pandemic. A greater number of the respondents 39.91% (n=97) normally go to work four days per week before this pandemic. Out of 243 respondents, 93.42% (n=227) said changed their working pattern for fear of contacting the infection (Table 2). Majority of the respondents 73.66% (n=179) strongly disagreed that their health care facility is prepared to handle and manage covid-19 outbreak. The majority of the respondents 42.32% (n= 103) somewhat agreed that hospital infection control policy in their facility was adequate. Out of 243 respondents, 77.78% (n=189) said they had restricted relation with their colleagues at work during the pandemic (Table 2).

Respondents means of transportation to work and place of residence

Table 3 shows the respondents’ means of transportation to work and place of residence. Out of 243 respondents, 81.48% (n=198) agreed that their ability to get to work safely was a matter of their concern. Those that get to their work place by means of public transport were highest 57.20% (n=139). The majority of the respondents 90.12% (n=219) lived outside their work place. Greater number of the respondents 71.19% (n=173) perceived their living outside the hospital environment as enough reason to stay away from work especially during the pandemic when you think vis-a-vis of how to get to work (Table 3).

| Respondents means of transportation to work and place of residence |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| a) Transportation to work |

|

|

| Do you think your ability to get to work safely is a matter of concern to you? |

|

|

| Yes |

198 |

81.48 |

| No |

45 |

81.52 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| By what means do you get to your work place? |

|

|

| Private car |

93 |

38.27 |

| Public transport |

139 |

57.2 |

| Trekking |

11 |

4.53 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Do you think going to work in public transport should be avoided during this pandemic? |

|

|

| Yes |

210 |

86.42 |

| No |

33 |

13.58 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Is there other means of transportation other than public/private |

|

|

| Yes |

13 |

4.11 |

| No |

233 |

95.89 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| b) Residence |

|

|

| Where do you live? |

|

|

| Inside the health care facility |

24 |

9.88 |

| outside |

219 |

90.12 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Do you think living outside the hospital environment is enough reason to stay away from work especially these days of the pandemic when you think vis-a-vis of how to get to work? |

|

|

| Yes |

173 |

71.19 |

| No |

70 |

28.81 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

Table 3 Respondents means of transportation to work and place of residence.

Ways to increase the respondents' willingness to work and mitigate absenteeism from work

From Table 4, which show the ways to increase the respondents’ willingness to work and mitigate absenteeism from work, revealed that out of 243 respondents, 98.33% (n=239) agreed that the respondents should beprovided with monetary inducement. The majority of the respondents 81.48% (n=198) agreed that professional bodies and unions incorporated in the provision of guidelines will increased their willingness to work. The majority of the respondents 97.53% (n=237) perceived the provision of cars or car loans to health care workers as a means of militating against healthcare workers absenteeism from work (Table 4).

| Ways to increased the respondents willingness to work and mitigate absenteeism from work |

Frequency(n) |

Percentage (%) |

| a) How can willingness to work be increased |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Yes |

239 |

98.35 |

| No |

4 |

1.65 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Having trust in the institution will increase willingness |

|

|

| Yes |

198 |

|

| no |

45 |

|

| Total |

243 |

|

| Professional bodies and unions should be incorporated in the provision of guidelines |

|

|

| Yes |

273 |

81.48 |

| no |

6 |

18.52 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| b) How can absenteeism be mitigated |

|

|

| Provision of cars or car loans to health care workers |

|

|

| Yes |

241 |

97.53 |

| No |

2 |

2.47 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Provision of specially arranged vehicle to convey health workers to and from the health facility. |

|

|

| Yes |

241 |

99.18 |

| No |

2 |

0.82 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Provision of accommodation within the health facility for all or key health workers. |

|

|

| Yes |

243 |

100 |

| No |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Provision of accommodation within the health facility for all or key health workers. |

|

|

| Yes |

243 |

100 |

| No |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

| Provide insurance scheme for health care workers in case of death in active service. |

|

|

| Yes |

243 |

100 |

| No |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

243 |

100 |

Table 4 Ways to increased the respondents willingness to work and mitigate absenteeism from work.

Discussion

Willingness of HCWs to respond to a pandemic is an essential component of health care preparedness to tackle a medical emergency. The treat of the second phase of the covid-19 pandemic is worrisome and evaluation of barriers that could militate against HCWs willingness to work is indispensable. The results of our study on the respondents’ knowledge of their responsibility and job as health care workers clearly showed that majority of the respondents knew their professional ethic and understood that they could be called upon to attend to the patients even during a pandemic like covid-19. A greater proportion of the respondents perceived themselves to be efficient to discharge their duties and also agreed that their roles are very essential especially during pandemic. These findings are not in agreement with the findings of the studies conducted by Barnett et al [17], Shaw et al [18] and Ives et al [19]. In their studies, they reported less than 50% of the respondents who were willing to work during a pandemic. The difference in our findings could be ascribed to the difference in the nature of our studies and geographical variations.

Our results on respondents’ perception of risk of working during covid-19 pandemic revealed that majority of the respondents perceived themselves to be at risk of infection going to work during the pandemic and that this has greatly affected their willingness to go to work. These findings are in keeping with findings of similar studies conducted by Ogolodom et al [2] on knowledge, attitude and fears of HCWs towards covid-19 pandemic and Balicer et al [20] on local public HCWs perceptions towards response to influenza pandemic. These findings imply that the risk perceptions have a great influence on the HCWs willingness to work during the novel covid-19 pandemic.

There was a statistically significant relationship between the years of experience and the respondents’ willingness to work during covid-19 pandemic. This implies that the willingness of the HCWs to work during covid-19 pandemic depends on their years of experience, meaning that those with higher working experience were highly willing to work during a pandemic when compared with people with lower years of working experience. This findings is in harmony with the observation noted in study conducted by Gee and Skovdal [12], According to Gee and Skovdal [12], high working experience are modifiers of risk perception, indicating that high working experience could act as a catalyst to willingness to work during a pandemic.

The respondents’ working pattern and work place safety were assessed and the results showed that majority of them had reduced the number of days they go to work during the pandemic when compared to the pre-covid-19 pandemic days. This could be attributed to the fact that a greater proportion of the respondents perceived their healthcare facility as unsafe and unprepared to handle and manage covid-19 outbreak. These findings are consistent with the results of the studies conducted by Ogolodom et al [2], Annan et al [11] and Barnett et al [17]. According to Barnett et al [17] study, such ratings of the healthcare facilities by greater numbers of the respondents is an indication of lack of confidence in their facilities preparedness and readiness of the hospitals to handle potentially epidemic prone diseases.

Our results on the means of transportation to work and place of residence of the health care workers showed that over 80% of the respondents perceived that their ability to get to work safely was a matter of concern to them, as majority of them usually goes to work by means of public transportation. Greater number of them live outside the healthcare facilities and this has greatly influenced their willingness to go to work during the pandemic. These findings are in consonance with similar observations documented by Draper et al [21] study on HCWs attitude towards working during influenza pandemic, noted that identifying types of provision such as housing at healthcare facilities for HCWs that would keep pools of nearby staff high, would help to resolve the travel problems and limit risks to workers and their families. Contrary to our findings, Barnett et al [17] study, reported that only 15% of their respondents felt they could not safely go to work. The discrepancies noted in our results could be ascribed to the fact that in our study, the majority of our respondents go to work by means of public transportation.

The results of the ways to increase willingness to work and mitigate absenteeism from work, showed that majority of the respondent perceived provision of monetary inducement, and incorporation of professional bodies and unions into the pandemic protocols formulation committee will help to increase their willingness to work during a pandemic. The respondents accounting for over 96% perceived provision of cars or car loans to HCWs as inducement to mitigate voluntary absenteeism from work. Despite the difference in the nature of our studies and the sample sizes, the findings of this study is in resonance with the findings of related studies carried out by Annan et al [11], Aoyagi et al [22], Ives et al [19] and Department of health[23].

A number of recommendations were made by our respondents as the way forward. These include promotion of health care workers, increase remunerations, provision of specially arranged transportation services, welfare packages, life insurance, personal protective equipment (PPE) and training among others.

Conclusion

The study revealed a strong sense of duty among the HCWs in time of a pandemic even with threat to their lives. The barriers to willingness to work as shown in this work included fears of work place safety and level of preparedness of the healthcare facility to handle a medical emergency. Public transportation and living outside the healthcare facility were also seen as obstacles to willingness to work during a pandemic. However, a multitude of approaches to increase willingness and mitigate voluntary absenteeism from work were suggested and these include addressing social factors such as need for transportation or housing that allows for social distancing. It is hoped that the findings of this study will be found useful by the government and relevant agencies to design and implement policies that will focus on and promote HCWs willingness to work during a pandemic like covid-19.

Conflicts of Interest

None was declared among the authors.

35447

References

- Zhong B, Luo W, Li H, Zhang Q, Liu X, et al. (2020) Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci 16: 1745-1752.

- Ogolodom MP, Mbaba AN, Alazigha N, Erondu OF, Egbe NO, et al. (2020) Knowledge, Attitudes and Fears of HealthCare Workers towards the Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic in South-South, Nigeria. Health Sci J 1:002.

- World Health Organization (2020) Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020.

- Li Y, Wang H, Jin XR, Li X, Pender M, et al. (2018) Experiences and challenges in the health protection of medical teams in the Chinese Ebola treatment center, Liberia: a qualitative study. Infect Dis Poverty 7: 92.

- Matsuishi K, Kawazoe A, Imai H, Ito A, Mouri K, et al. (2012) Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 66: 353-360.

- Orentlicher D (2018) The Physician’s Duty to Treat During Pandemics. Am J Public Health 108: 1459-1461.

- Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, Joshi AD, Guo C, et al. (2020) Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 5: e475-483.

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team (2020) Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19: United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69: 477-481.

- Lazzerini M, Putoto G (2020) COVID-19 in Italy: momentous decisions and many uncertainties. Lancet Glob Health 8: e641-42.

- Chaffee M (2006) Making the decision to report to work in a disaster. Am J Nurs 106:54-57.

- Annan AA, Yar DD, Owusu M, Biney EA, Forson P, et al. (2017) Health care workers indicate ill-preparedness for Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in Ashanti Region of Ghana. BMC Public Health 17:546.

- Gee S, Skovdal M (2017) The role of risk perception in willingness to respond to the 2014–2016 West African Ebola outbreak: a qualitative study of international health care workers. Glob Health Res Policy 2:21

- Stein BD, Tanielian TL, Eisenman DP, Keyser DJ, Burnam MA, et al. (2004) Emotional and behavioral consequences of bioterrorism: planning a public health response. Milbank Q 82: 413-455.

- Ehrenstein BP, Hanses F, Salzberger B (2006) Influenza pandemic and professional duty: family or patient's first? A qualitative survey of hospital employees. BMC Public Health 6:311.

- Zewudie A, Regasa T, Kebede O, Abebe L, Feyissa D, et al. (2021) Healthcare Professionals’ Willingness and Preparedness to Work During ssCOVID-19 in Selected Hospitals of Southwest Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 14: 391-404.

- Turner RC, Carlson L (2003) Indexes of item-objective congruence for multidimensional items. Int J Test 3: 163-171.

- Barnett DJ, Balicer RD, Thompson CB, Storey JD, Omer SB, et al. (2009) Assessment of Local Public Health Workers’ Willingness to Respond to Pandemic; Influenza through Application of the Extended Parallel Process Model. PLoS ONE 4: e6365.

- Shaw KA, Chilcott A, Hansen E, Winzenberg T (2006) The GP’s response to pandemic influenza: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 23:267-272.

- Ives J, Greenfield S, Parry JM, Draper H, Gratus C, et al. (2009) Healthcare workers' attitudes to working during pandemic influenza: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 9:56.

- Balicer RD, Omer SB, Barnett DJ, Everly GS Jr (2006) Local public health workers’ perceptions toward responding to an influenza pandemic. BMC Public Health 18:6-99.

- Draper H, Wilson S, Ives J, Gratus C, Greenfield S, et al.(2008) Healthcare workers' attitudes towards working during pandemic influenza: A multi method study. BMC Public Health 8:192.

- Aoyagi Y, Beck CR, Dingwall R, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS (2015) Healthcare workers’ willingness to work during an influenza pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 9: 120-130.

- (2009) Pandemic Influenza: Guidance on Preparing Acute Hospitals in England. Wilmington Healthcare Limited.