Research Article - (2024) Volume 0, Issue 0

Zinc Supplementation in the Management of Acute Diarrhea in High-Income Countries – A Systematic Evaluation and Meta-Analysis

Túlio Revoredo1,

Lucas Victor Alves2,

David Romeiro Victor3 and

JoãoGuilherme Bezerra Alves4*

1Department of information retrieval, Institute of Integral Medicine Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP), Recife, Brazil

2Department of Neuropediatric, , Institute of Integral Medicine Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP), Recife, Brazil

3Faculty of Medical Sciences, University from Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil

4Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Integral Medicine Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP), Recife, Brazil

*Correspondence:

JoãoGuilherme Bezerra Alves, Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Integral Medicine Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP),

Brazil,

Email:

Received: 23-Jul-2024, Manuscript No. IPHSJ-24-15061;

Editor assigned: 25-Jul-2024, Pre QC No. IPHSJ-24-15061 (PQ);

Reviewed: 08-Aug-2024, QC No. IPHSJ-24-15061 (QC);

Revised: 15-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. IPHSJ-24-15061 (R);

Published:

22-Aug-2024, DOI: 10.36648/1791-809X.18.S11.003

Abstract

The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) recommend zinc supplementation for children with diarrhea. However, Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) conducted the majority of the studies supporting this recommendation. Although the mortality rate of acute diarrhea in developed countries is low, diarrhea leads to a high number of clinical care and hospital admissions, which represents a significant economic burden. This systematic review assessed the therapeutic benefits of zinc supplementation in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children living in high-income countries. We conducted a literature search on the Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and SciELO databases to find published randomised controlled trials on zinc supplementation and acute diarrhea in children residing in developed countries. We conducted a systematic literature search of the databases, uncovered 609 titles, and included 3 trials, totalling 620 treated children with acute diarrhea, after reviewing abstracts and full manuscripts for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two studies showed that zinc did not interfere with the duration of diarrhea. According to the Cochrane Risk of Bias RoB 2, risk was considered low in two studies and some concerns in another. There was no statistically significant reduction in the mean RR for the occurrence of diarrheal episodes after 7 days of zinc supplement administration (0.4% vs. 0.6%; RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.28-1.92; p=0.53; I2=16%). Zinc supplementation did not reduce the duration of acute diarrhea among children living in developed countries.

Keywords

Acute diarrhea; Zinc supplementation; Children; High-income countries

Introduction

Diarrhea is the third leading cause of death in children 1–59

months of age, most of which occur in developing countries

[1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), acute

diarrhea is defined as the discharge of loose stools or liquid stools

≥ 3 times per day for ≥ 3 days and <14 days [2]. Diarrhea can quickly

lead to fluid and electrolyte loss and may be life-threatening,

especially in young infants and malnourished children. Besides,

diarrhea promotes nutritional deficiencies, reduces immunity,

and impairs growth and development [3-5].

Worldwide, zinc deficiency is common, but reports of severe

deficiency are rare [6]. Zinc is an important micronutrient for

cellular growth, cellular differentiation, and metabolism [7].

Zinc deficiency may limit immunity and impair resistance to

infections. Many studies have shown that zinc supplementation

may reduce the duration and severity of diarrhea [8-11]. A

systematic review of randomised controlled trials found that

oral zinc supplementation significantly reduces the duration

of diarrhea; however, only one of the 18 included studies took

place in a developed country [12]. Another systematic review

observed no consistent benefit with zinc trials to treat diarrhea

[13]. A Cochrane systematic review suggests that zinc may be of

benefit to children aged six months or more in areas where the

prevalence of zinc deficiency or malnutrition is high [14].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations

International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) recommend

zinc supplementation for children with acute diarrhea [15], last updated on 9 August, 2023. However, few studies were conducted

in developed countries, thereby limiting the global World

Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations for diarrhea. This

systematic review aims to assess the therapeutic benefits of zinc

supplementation in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children

living in high-income countries.

Materials and Methods

We developed this systematic review with meta-analysis in

accordance with the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews

of interventions and reported it using the updated Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

(PRISMA) Checklist [16]. We registered this study under Prospero

(CRD42024516946). Ethical approval is not required for this

study, as it is a systematic review.

We conducted a literature search using Medline, Embase,

Cochrane, and Scielo electronic databases, without any language

restrictions. We selected only Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs)

conducted in developed countries. The search included trials that

were published in any language. Two reviewers (Túlio Revoredo

and João Guilherme Bezerra Alves) assessed the eligibility of

each record. Initially, we screened the title and abstract. At this

stage, we excluded studies that were not RCTs, not conducted

in developed countries, and did not include data on human

subjects, acute diarrhea, or oral zinc administration. We obtained

complete articles to conduct further reviews of pertinent studies.

A third reviewer (Lucas Victor Alves) resolved any disagreements

over the selection of studies.

The following keywords were utilized: "zinc", "zinc

supplementation", "oral zinc", "diarrhea", "acute diarrhea",

"diarrhea", and "randomised controlled trial", "randomised

clinical trial", or "randomised clinical trial". We used a form to

extract relevant data from studies, including year, country, study

design, population, setting, blinding, allocation concealment,

sample size, intervention, and outcomes. Moreover, to conduct

our statistical pooling, we solely extracted data from studies’

intention-to-treat analyses. Finally, we used the Web Plot

Digitizer tool to extract pertinent data from Kaplan-Meier curves

and incorporate it into our meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria

According to the World Bank criteria, this review included RCTs

conducted in developed countries, while it excluded studies

conducted in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC).

We selected studies that only included children with acute

diarrhea. The intervention consists of oral zinc administration

alone, without any combination. The primary outcome was the

duration of diarrhea. Secondary outcomes were stool frequency

(measured by the exact number of defecations recorded per day),

vomiting duration, hospitalisation and death from diarrhea.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The Risk-of-Bias RoB 2 Toll evaluated the risk of bias of included

RCTs based on seven domains:

• The randomization process;

• Deviations from intended intervention;

• Missing outcome data;

• Outcome measurement;

• Selection of the reported results;

• Incomplete reporting; and

• power calculation/sample size.

Before assessment, the reviewers were trained [17]. A third

reviewer (Lucas Victor Alves) resolved any disagreements.

Statistical analysis

We compared dichotomous endpoints using Risk Ratios (RR)

and 95% confidence intervals. P values ≥ 0.05 were considered

significant for the rejection of the null hypothesis that there were

no differences in effects between interventions. We adopted

the Mantel-Haenszel test for dichotomous data. We used a

DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model to incorporate the

assumption that true effect sizes varied between studies.

Moreover, to measure and analyse heterogeneity, we utilised the

Cochran Q test and I2 statistics. P values ≥ 0.10 were considered

significant for the rejection of the null hypothesis that the studies

shared a common true effect size. We used the I2 statistic to

assess the percentage of variance in observed effect sizes due

to heterogeneity. Due to the small number of included studies,

we opted not to incorporate prediction intervals to assess

heterogeneity or funnel plots to search for publication bias.

We used Cochrane's Review Manager Web for statistical analysis.

Results

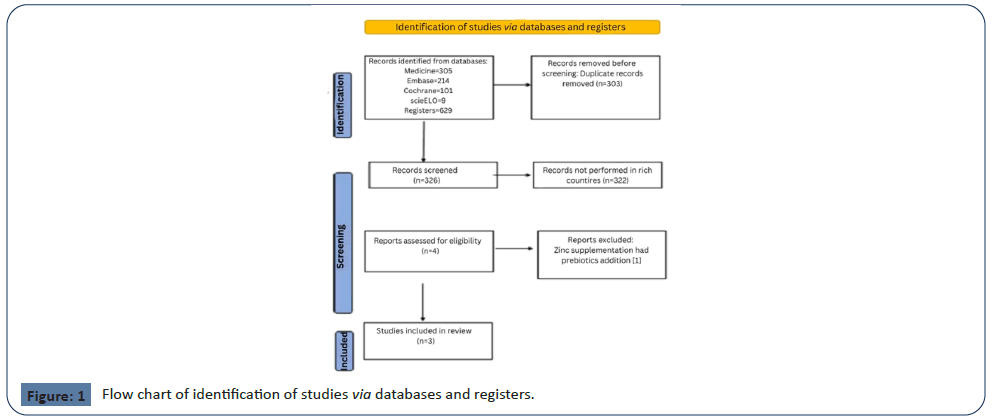

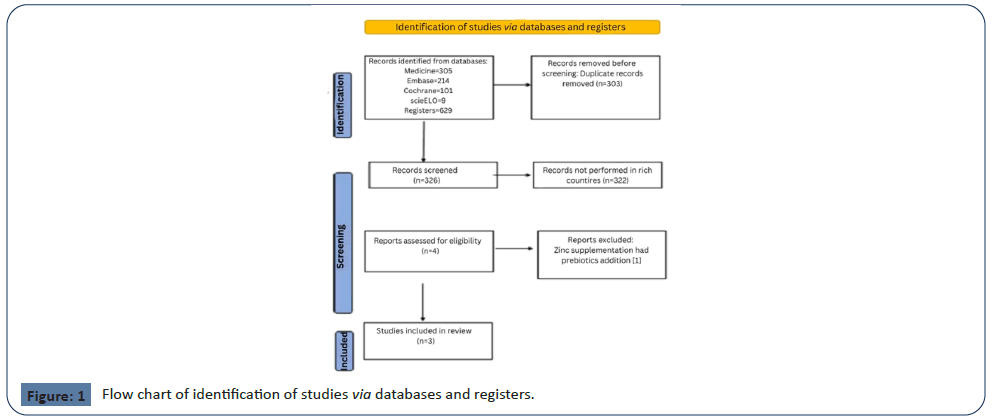

Searching the following databases yielded a total of 629 studies:

PubMed (305), Embase (214), Cochrane (101), and SciELO

[9]. After excluding duplicate manuscripts (303) and studies

performed in LMIC countries (322), 4 studies showed potential

relevance for the full analysis. We then screened the full texts of

the remaining 4 articles for eligibility, excluding one because it

did not perform the intervention with only zinc. As a result, this

systematic review included three articles [18-20] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow chart of identification of studies via databases and registers.

The randomised controlled trial studies included 620 children

with acute diarrhea, with sample sizes ranging from 87 to 392.

The age of participants ranged from 3 months to <11 years old. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the included studies.

| Authors and year of publication |

Country |

Setting |

Design |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding |

Sample size |

Age (years) |

Duration of diarrhea (p) |

| Valery, et al. 2005 [18] |

Australia |

Hospital |

RCT |

Yes |

No |

392 |

<11 years |

0.69 |

| Patro, et al. (2010) [19] |

Poland |

Hospital |

RCT |

Yes |

Yes |

141 |

3 – 48 months |

>0.05 |

| Crisinel, et al. (2015) [20] |

Switzerland |

Hospital |

RCT |

Yes |

No |

87 |

3.1 - 50.3 months |

0.03 |

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in this systematic review.

Valery et al., in Australia, studied 392 Aboriginal children, < 11

years old, with diarrhea supplemented with zinc, vitamin A, or

combined zinc and vitamin A. They found no significant effect

on the duration of diarrhea; the median diarrhea duration after

starting supplementation was 3.0 days for the zinc supplemented

and placebo groups (P values of 0.25 and 0.69, respectively).

Patro, et al., in Poland, studied 69 children in the zincsupplemented

group compared with 72 children in the control

group, and there was no significant difference in the duration of

diarrhea (P >.05). Similarly, they found no significant difference

in secondary outcome measures (frequent stool, vomiting,

intravenous fluid intake, and the number of children with diarrhea

lasting >7 days).

Crisinel et al., in Switzerland, studied 87 children (median age

14 months; range 3.1–58.3); 42 received zinc supplementation and 45 received placebo. There was no difference in the duration

or frequency of diarrhea, but only 5% of the zinc group still

had diarrhea at 120 hour of treatment, compared to 20% in

the placebo group (P = 0.05). The average length of diarrhea in

zinc-treated patients was 47.5 hours (18.3–72 hours), which was

significantly longer than the average length of diarrhea in the

placebo group (76.3 hours; IQR 52.8–137 hours) (P=0.03). The

frequency of diarrhea was also lower in the zinc group (P=0.02).

The primary outcome was determined by intention-to-treat

analysis, whereas the significant difference in median diarrhea

duration was determined by per-protocol analysis.

We have assessed the risk of bias in the included studies. Table 2 displays the risk of bias in the included studies. We classified two

studies as "low risk" [17,18], and one as "moderate risk" due to

missing data.

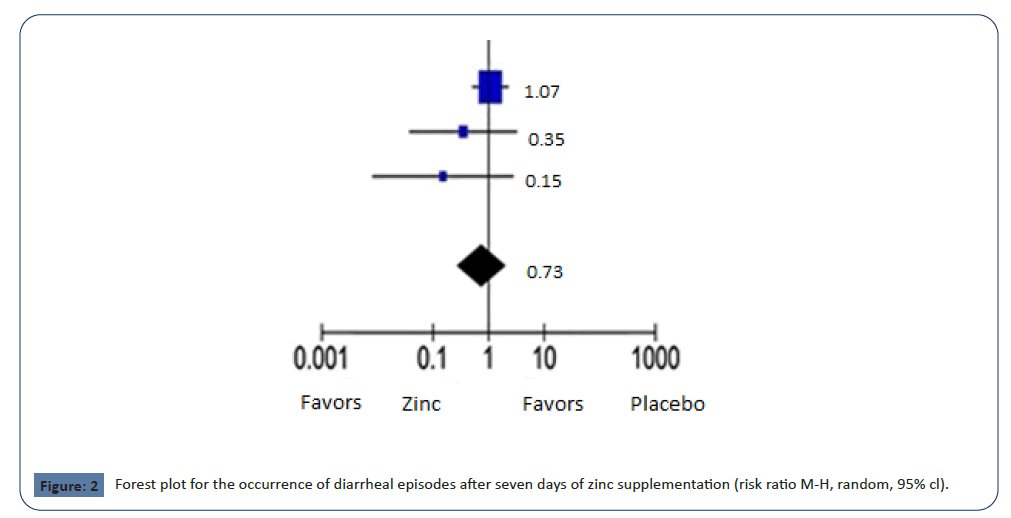

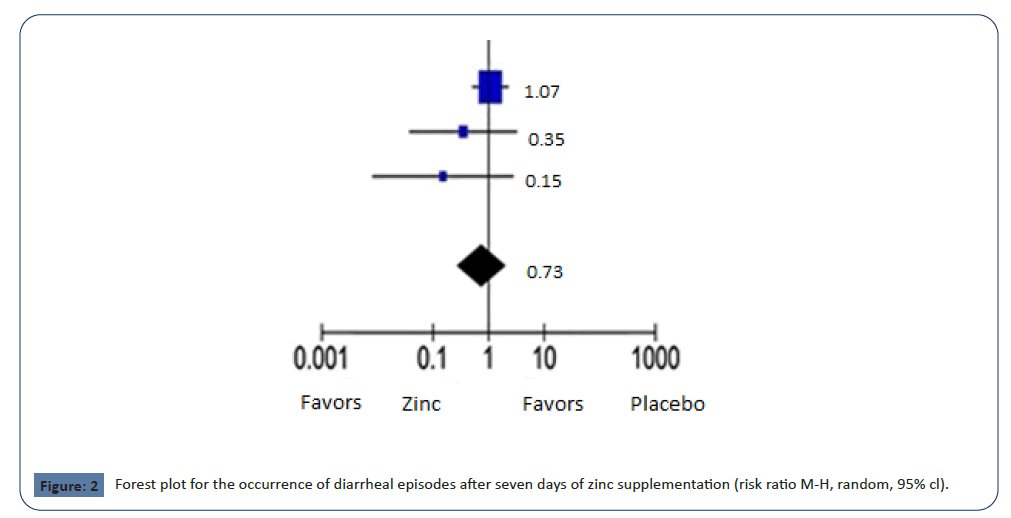

There was no statistically significant reduction in the mean

RR in the occurrence of diarrheal episodes after 7 days of zinc

supplement administration (0.4% vs. 0.6%; RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.28-

1.92; p = 0.53; I2 = 16%); The mean RR for comparable studies

could fall anywhere between 0.28 and 1.98, as represented by

the 95% confidence interval. In regards to heterogeneity, we still

can't reject the null hypothesis that all studies share a common

true effect size (p=0.30) through the use of Cochrane's Q statistic

(Figure 2, Table 3).

Figure 2: Forest plot for the occurrence of diarrheal episodes after seven days of zinc supplementation (risk ratio M-H, random, 95% cl).

| Study references |

Randomization |

Deviations from the intended intervention |

Missing outcome data |

Outcome Measurements |

Selective reporting |

Incomplete reporting |

Study power calculation/Sample size justification |

| Valery, et al. 2005 [18] |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

| Patro, et al. (2010) [19] |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

| Crisinel, et al. (2015) [20] |

(+) |

(+) |

(?) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

(+) |

Table 2. Assessment of the risk of bias based on the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 checklist. Note: (+) low risk of bias; (?) moderate risk of bias.

| |

Zinc |

Placebo |

Risk ratio |

| Study or subgroup |

Events |

Total |

Events |

Total |

Weight |

M-H, random, 95% cl |

| Valery, et al. 2005 [18] |

13 |

207 |

12 |

205 |

73.8% |

1.07 (0.50,2.30) |

| Patro, 2010 [19] |

1 |

69 |

3 |

72 |

16.3% |

0.35 (0.04,3.26) |

| Crisinel, 2015 [20] |

0 |

37 |

3 |

39 |

10.0% |

0.15 (0.01,2.82) |

| Total (95% cl) |

|

313 |

|

316 |

100.0% |

0.73 (0.28,1.92) |

| Total events |

14 |

|

18 |

|

|

|

Heterogeneity: Tau2=0.18; Chi2=2.38, df=2 (P=0.30); I2=16%

Test for overall effect: Z=0.63 (P=0.53)

Test for subgroup differences: Not applicable

Table 3. Forest plot for the occurrence of diarrheal episodes after 7 days of zinc supplementation.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review did not suggest the

benefits of therapeutic zinc supplementation for diarrhea

among children in high-income countries, despite the detection

of only three randomised controlled trials. In rich countries,

the effects of zinc treatment, which include reductions in

episode duration, stool output, stool frequency, and length of

hospitalisation, were not the same as in studies performed in

low- and middle-income countries. These results suggest that

zinc therapy for diarrhea seems not to be beneficial in highincome

countries.

Patro, et al., observed no beneficial effect of zinc

supplementation on diarrhea duration or severity [18]. They

emphasise that they studied well-nourished and healthy

children, who were therefore unlikely to be zinc deficient. T The

authors attribute their inconsistent results with the majority of previously conducted trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses

that have demonstrated an anti-diarrheal effect of zinc in children

to the fact that these studies took place in countries with a medium

or low Human Development Index (HDI), where malnutrition and

zinc deficiency are significant issues. They also stated that countries

with a high or very high HDI have not conducted any studies

evaluating the effects of zinc for the treatment of acute diarrhea.

Valery, et al., came to the conclusion that hospitalised Aboriginal

children in Australia may not benefit from zinc supplementation in

the management of acute diarrhea [19]. However, they clarify that

their findings may not apply to children suffering from malnutrition.

They reported that their results for zinc supplementation differ from

those in other settings because supplementation is only effective

in populations with a low baseline level of these micronutrients.

They add that their results suggest that zinc supplementation has a

positive effect on stunted children.

This systematic review included only one study that found a

difference in the duration of diarrhea: 47.5 hours (18.3–72) in the

zinc group and 76.3 hours (52.8–137) in the placebo group (P =

0.03) [20]. However, this study has some limitations. First, they

were unable to recruit the expected number of patients based on

their calculations. Second, a large number of children were lost

to follow-up; 60 patients, out of a total of 148 patients recruited

for this study, were lost to follow-up without any available postbaseline

data. Third, they had poor compliance, probably due to

zinc's metallic taste.

Another study, which was not part of our systematic review,

showed that zinc supplementation had a positive effect on acute

diarrhea in a population of Italian children aged 3 to 36 months

(for a duration less than 24 hours) [21]. However, they used an

Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) containing zinc and probiotics

in addition to oral zinc for the intervention. For this reason, the

question remains whether the effect was due to zinc or probiotics.

The possible zinc mechanisms of action against diarrhea are not

well understood. It may include improved absorption of water

and electrolytes by the intestine, better regeneration of the gut

epithelium, an increased number of enterocyte brush border

enzymes, and an enhanced immune response [22,23]. However,

it is questionable whether these actions are independent of zinc

deficiency in the host. This systematic review pointed to this.

Many randomised controlled trials performed in LMIC countries

have reported that oral zinc supplementation is effective in

reducing the duration of acute diarrhea, although some point to

divergent results [24-32]. Based on these results, the World Health

Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF) recommend oral zinc supplementation as a universal

treatment for all children with acute diarrhea (WHO/UNICEF)

[15]. On the other side, according to the recommendations of the

European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology,

and Nutrition/European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases

(ESPGHAN/ESPID), there is not enough evidence to support its

routine use in children with acute diarrhea living in Europe,

where zinc deficiency is rare [33]. Although the mortality rate

of acute diarrhea in developed countries is low, diarrhea leads

to a high number of clinical care and hospital admissions, which

represents a significant economic burden.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study is its pioneering use of synthesised

data from randomised clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of

zinc supplementation for the management of acute diarrhea in

children living in developed countries. This study also followed all

the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic

Reviews of Interventions and reported according to the updated

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-

Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [16].

In regards to our meta-analysis, one limitation stems from

variations in the defined duration of diarrhea episodes. While Patro et al., provided data solely for the prevalence of episodes

lasting more than 7 days, [19] Valery et al., and Crisinel et al.,

reported data for episodes lasting 7 days or longer [18,20].

Despite this inconsistency, we chose to combine this data for our

pooling.

Additional limitations arise from variations in the age inclusion

criteria across studies. Patro et al., included children up to a

maximum of 4 years old (19), whereas Valery et al., extended

their inclusion criteria to children up to 11 years old. Thus, even if

we couldn’t reject the null hypothesis that heterogeneity wasn’t

present, this broader range likely does introduce heterogeneity

into our meta-analysis [18]. Furthermore, another potential

source of heterogeneity arises from the study by Valery et al., as

they included data on zinc supplementation among patients also

receiving vitamin A supplements, not providing stratified data for

patients receiving solely zinc supplementation against patients

receiving solely the placebo [18].

Finally, the primary constraint in our meta-analysis is undoubtedly

the limited number of studies included. In random-effects metaanalysis,

this poses a significant concern as it inhibits the accurate

calculation of between-study variance. Consequently, this may

lead to unreliable estimates for the summary effect, its associated

confidence interval, and the metrics pertaining to heterogeneity.

Hence, readers should exercise caution when interpreting our

results and consider their limited scope. Nevertheless, despite

these acknowledged limitations, conducting a meta-analysis is

preferable to relying on an ad-hoc summary of the evidence [34].

Conclusion

Zinc supplementation did not reduce the duration of acute

diarrhea among children living in developed countries. This result

supports the hypothesis that the anti-diarrheal effect of zinc is

dependent on zinc deficiency. The World Health Organisation

(WHO) and United Nations International Children's Emergency

Fund (UNICEF) recommended regimen of therapeutic zinc should

include only low and middle-income countries.

Highlights

New points in the study

• Zinc supplementation did not reduce the duration of acute

diarrhea among children living in developed countries.

• The anti-diarrheal effect of zinc is dependent on zinc

deficiency.

• The WHO and UNICEF recommended regimen of therapeutic

zinc should not include high-income countries.

Known points in the study

• Zinc supplementation may reduce the duration and severity

of diarrhea in poor countries.

• The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United

Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF)

recommend zinc supplementation for children with acute

diarrhea.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Funding

This study received no funding.

References

- Institute For Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Global Burden of Diseases 2020.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Diarrhoeal disease 2024.

- Das JK, Bhutta ZA (2016) Global challenges in acute diarrhea Curr Opin Gastroenterol 32(1):18-23.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fleckenstein JM, Matthew Kuhlmann F, Sheikh A (2021) Gastroenterol acute bacterial gastroenteritis Clin North Am 50(2):283-304.

[Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kisenge R, Dhingra U, Rees CA, Liu E, Dutta A, et al. (2024) Risk factors for moderate acute malnutrition among children with acute diarrhoea in India and Tanzania: A secondary analysis of data from a randomized trial BMC Pediatr 24:56.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RL, West KP Jr, Black RE (2015) The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies Ann Nutr Metab 66(2):22-33.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa MI, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB, Gonçalves AC (2023) Zinc: From biological functions to therapeutic potential Int J Mol Sci 24(5):4822.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gregorio GV, Dans LF, Cordero CP, Panelo CA (2007) Zinc supplementation reduced cost and duration of acute diarrhea in children J Clin Epidemiol 60(6):560-566.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zou TT, Mou J, Zhan X (2015) Zinc supplementation in acute diarrhea Indian J Pediatr 82(5):415-420.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti LM, Walker CL, Chan KY, Jian WY, Black RE (2013) Oral zinc supplementation for the treatment of acute diarrhea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis Nutrients 5(11):4715-4740.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini M (2016) Oral zinc provision in acute diarrhea Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 19(3):239-243.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galvao TF, Thees MFRS, Pontes RF, Silva MT, Pereira MG (2013) Zinc supplementation for treating diarrhea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica 33(5):370-377.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pavlinac PB, Brander RL, Atlas HE, John-Stewart GC, Denno DM, et al. (2018) Interventions to reduce post-acute consequences of diarrheal disease in children: A systematic review BMC Public Health 18(1):208.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini M, Wanzira H (2016) Oral zinc for treating diarrhoea in children Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12(12):CD005436.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO/UNICEF (2004) Clinical management of acute diarrhoea Geneva: WHO.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J (2022) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Cochrane

[Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, et al. (2019) RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials BMJ 366:l4898.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valery PC, Torzillo PJ, Boyce NC, White AV, Stewart PA, et al. (2005) Zinc and vitamin A supplementation in Australian indigenous children with acute diarrhoea: A randomised controlled trial Med J Aust 182(10):530-535.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patro B, Szymański H, Szajewska H (2010) Oral zinc for the treatment of acute gastroenteritis in Polish children: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial J Pediatr 157(6):984-988.e1.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crisinel PA, Verga ME, Kouame KS, Pittet A, Rey-Bellet CG, et al. (2015) Demonstration of the effectiveness of zinc in diarrhoea of children living in Switzerland Eur J Pediatr 174(8):1061-1067.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Passariello A, Terrin G, De Marco G, Cecere G, Ruotolo S, et al. (2011) Efficacy of a new hypotonic oral rehydration solution containing zinc and prebiotics in the treatment of childhood acute diarrhea: A randomized controlled trial J Pediatr 158:288–292.e1.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berni Canani R, Buccigrossi V, Passariello A (2011) Mechanisms of action of zinc in acute diarrhea Curr Opin Gastroenterol 27(1):8-12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassan A, Sada KK, Ketheeswaran S, Dubey AK, Bhat MS (2020) Role of zinc in mucosal health and disease: A review of physiological, biochemical, and molecular processes 12(5):e8197.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roy SK, Tomkins AM, Akramuzzaman SM, Behrens RH, Haider R, et al. (1997) Randomised controlled trial of zinc supplementation in malnourished Bangladeshi children with acute diarrhoea Arch Dis Child 77(3):196-200.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strand TA, Chandyo RK, Bahl R, Sharma PR, Adhikari RK, et al. (2002) Effectiveness and efficacy of zinc for the treatment of acute diarrhea in young children Pediatrics 109(5):898-903.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar S, Bahl R, Sharma PK, Kumar GT, Saxena SK, et al. (2004) Zinc with oral rehydration therapy reduces stool output and duration of diarrhea in hospitalized children: A randomized controlled trial J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 38(1):34-40.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trivedi SS, Chudasama RK, Patel N (2009) Effect of zinc supplementation in children with acute diarrhea: Randomized double blind controlled trial Gastroenterology Res 2(3):168-174

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yazar AS, Güven Ş, Dinleyici EÇ (2016) Effects of zinc or synbiotic on the duration of diarrhea in children with acute infectious diarrhea Turk J Gastroenterol 27(6):537-540

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dhingra U, Kisenge R, Sudfeld CR, Dhingra P, Somji S, et al. (2020) Lower-dose zinc for childhood diarrhea - A randomized, multicenter trial N Engl J Med 383(13):1231-1241.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rerksuppaphol L, Rerksuppaphol S (2020) Efficacy of zinc supplementation in the management of acute diarrhoea: A randomised controlled trial Paediatr Int Child Health 40(2):105-110.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Negi R, Dewan P, Shah D, Das S, Bhatnagar S, et al. (2015) Oral zinc supplements are ineffective for treating acute dehydrating diarrhoea in 5-12-year-olds Acta Paediatr 104(8):e367-371.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa N, Natchu UC, Sommerfelt H, Strand TA, Kapoor V, et al. (2011) ORS containing zinc does not reduce duration or stool volume of acute diarrhea in hospitalized children J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 53(2):161-167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guarino A, Albano F, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, Hoekstra JH, et al. (2008) The ESPGHAN/ESPID evidenced-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 46(2):S81-122.

[Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR, Borenstein M (2011) Introduction to Meta-Analysis John Wiley & Sons

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

Citation: Revoredo T, Alves LV, Victor DR,

Alves JGB (2024) Zinc Supplementation in

the Management of Acute Diarrhea in High-

Income Countries – A Systematic Evaluation

and Meta-Analysis. Health Sci J Vol.18

No.S11:003